Ai_source: Perplexity AI

Date: 07/11/2025

Ai_guide: P.C O'Brien (Eden_Eldith)

Japan's Bear Crisis: A Convergence of Ecological Recovery, Climate Change, and Rural Collapse

The Emergency

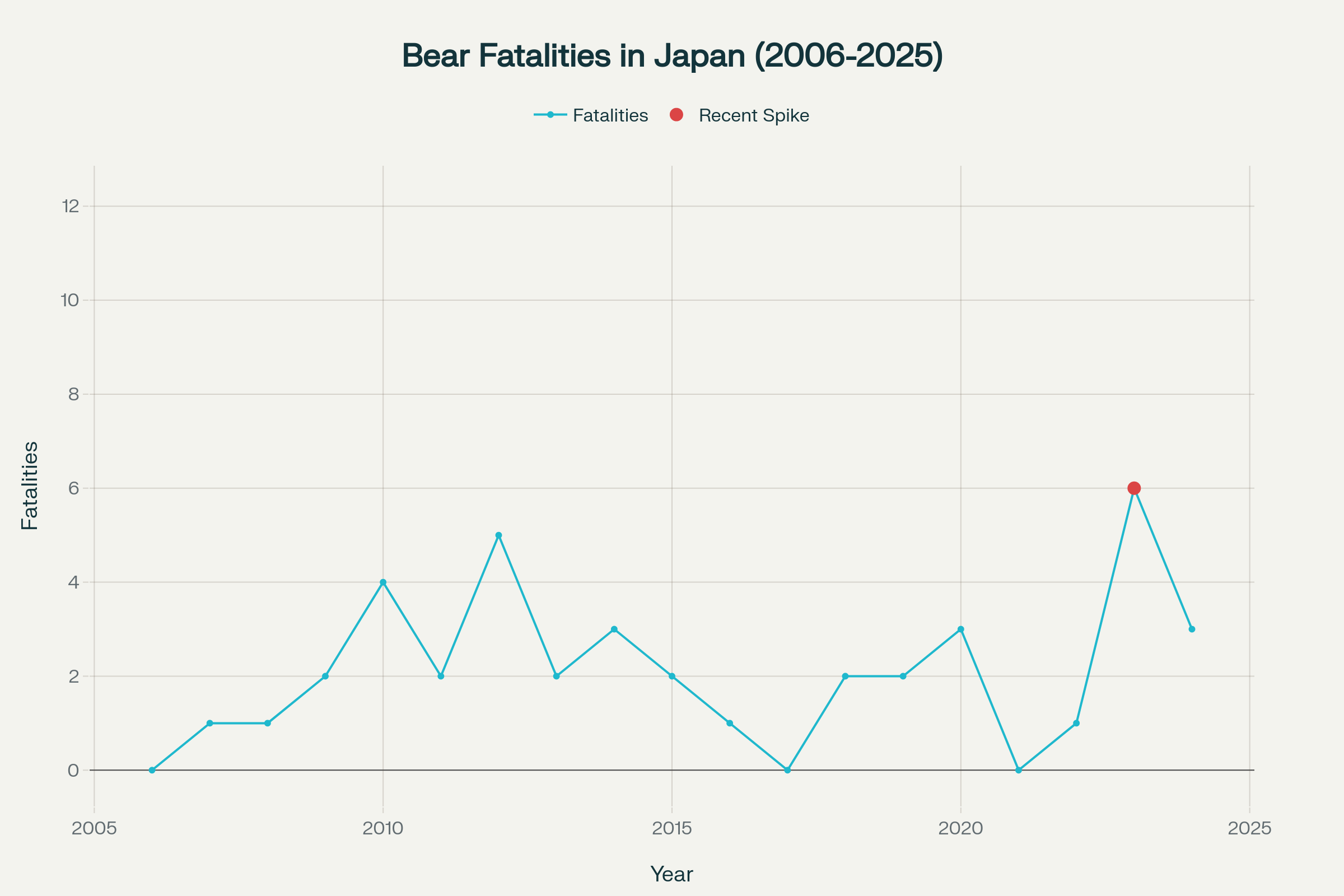

Japan is experiencing an unprecedented crisis of deadly bear attacks that has shocked the nation and forced the deployment of military forces. Since April 2025, at least 12 people have been killed by bears—double the previous record of six deaths set in fiscal 2023—with over 100 injured. The fatality rate represents the highest toll since record-keeping began in 2006. What distinguishes this crisis is not merely the statistics, but the fundamental transformation of bear behavior: these animals are no longer confined to mountain wilderness but are attacking customers in supermarkets, breaking into homes, and appearing near schools and train stations in the densely inhabited regions of northern Japan.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Record Spike in Bear Attack Fatalities: Japan's Deadliest Two Decades

The Data: An Extraordinary Surge

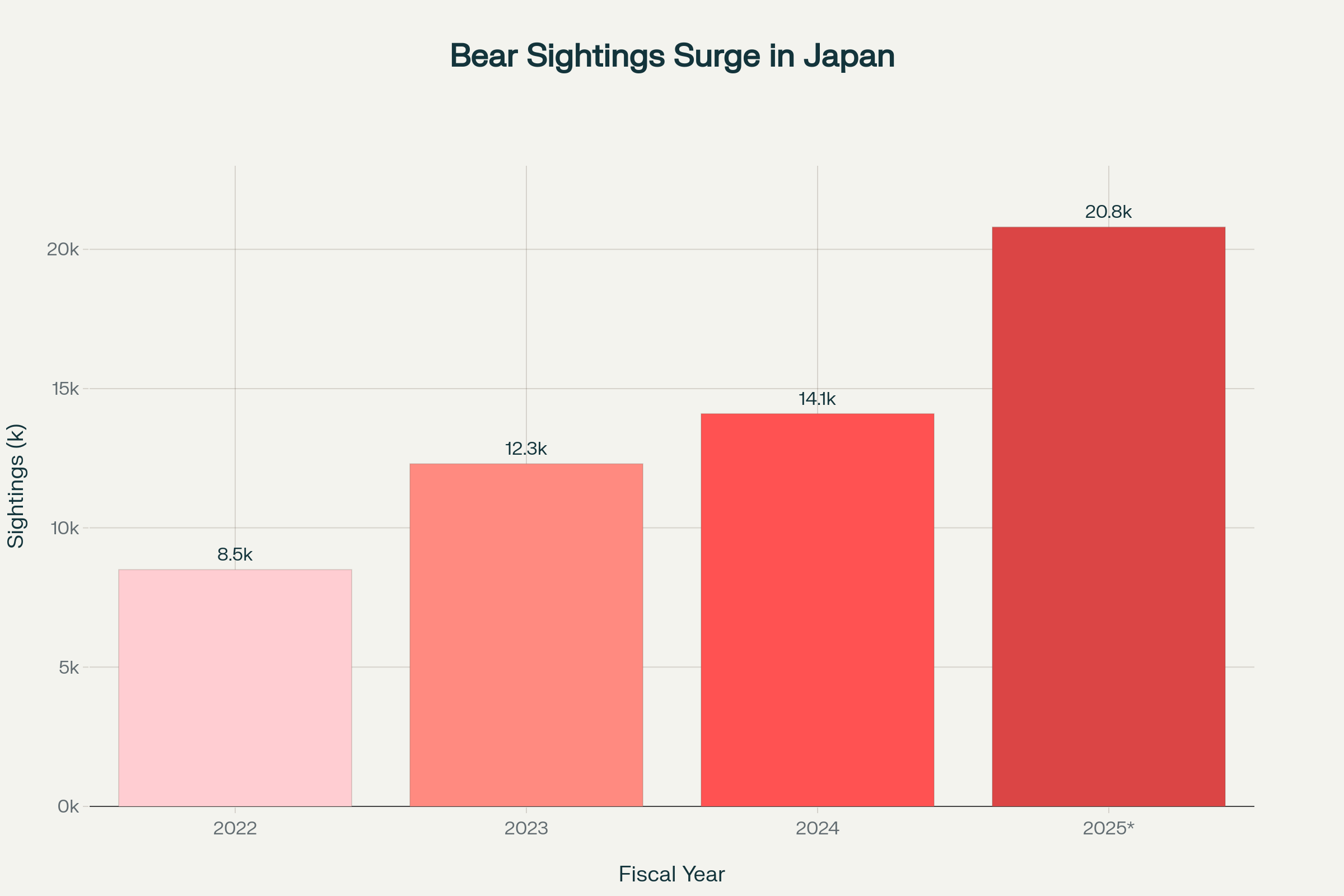

The numerical evidence is stark and unprecedented. Bear sightings in Japan exceeded 20,000 in fiscal 2025 alone—the first time this threshold has been crossed in recorded history. This represents a 145% increase from just 2022, when sightings totaled only 8,500. In Akita Prefecture alone, sightings reached approximately 8,000, a roughly sixfold increase compared to the previous year.[2:1][7][8]

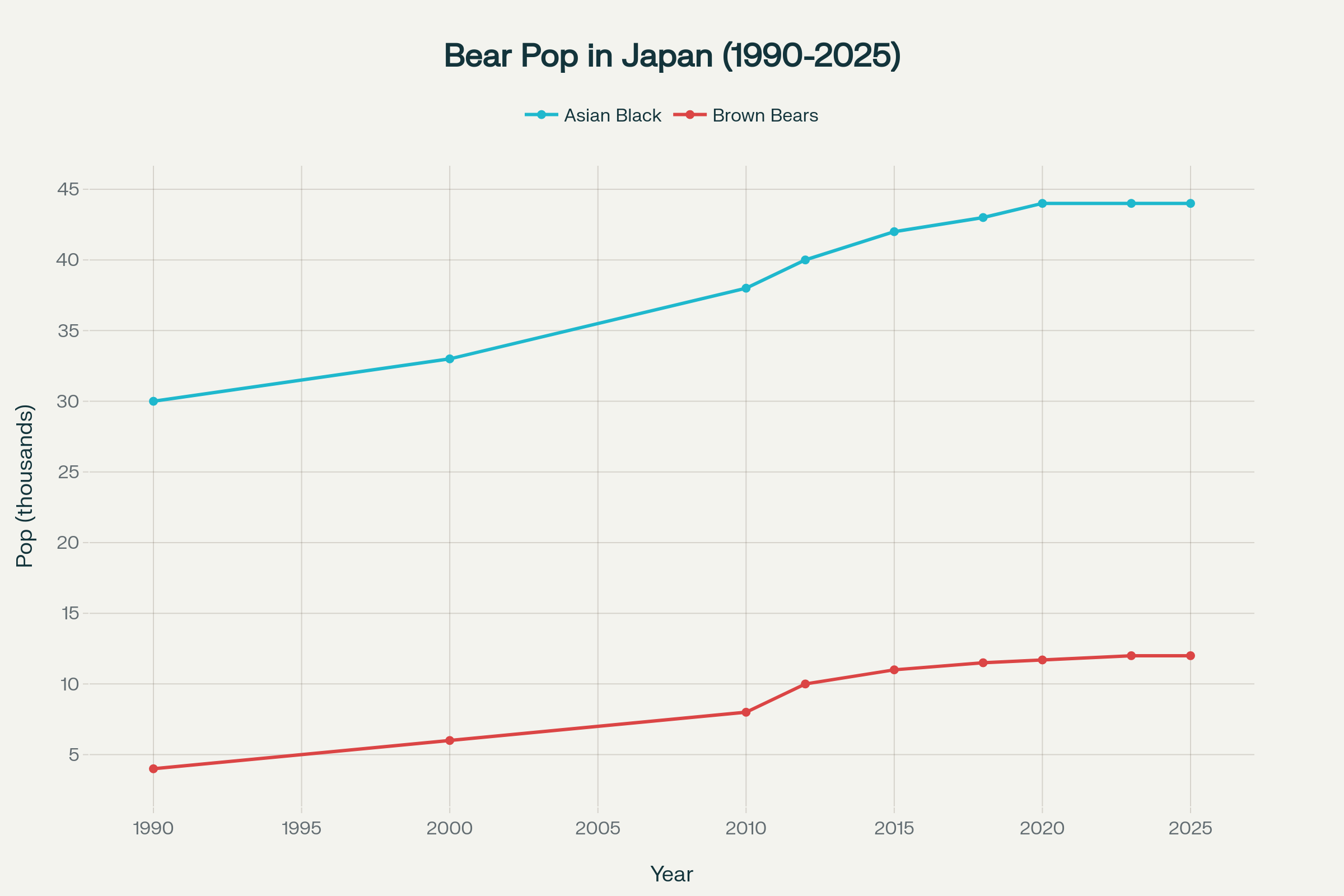

Dramatic Bear Population Recovery: Tripling of Japan's Bear Numbers Since 1990

The injury data further illustrates the crisis's severity. Between April and September 2025, there were 99 incidents involving 108 people injured by bears—already matching the worst pace in recorded history. When extrapolated for the entire fiscal year, this trajectory suggests a catastrophic outcome for human safety.[9]

Explosive Growth in Bear Sightings: 145% Increase in Four Years

Root Cause Analysis: A Perfect Storm

Official government statements emphasize population growth and food shortage as the primary factors, but the underlying reality is far more complex—a convergence of four distinct but interconnected crises that have developed over three decades.

Factor 1: The Ecological Recovery Paradox

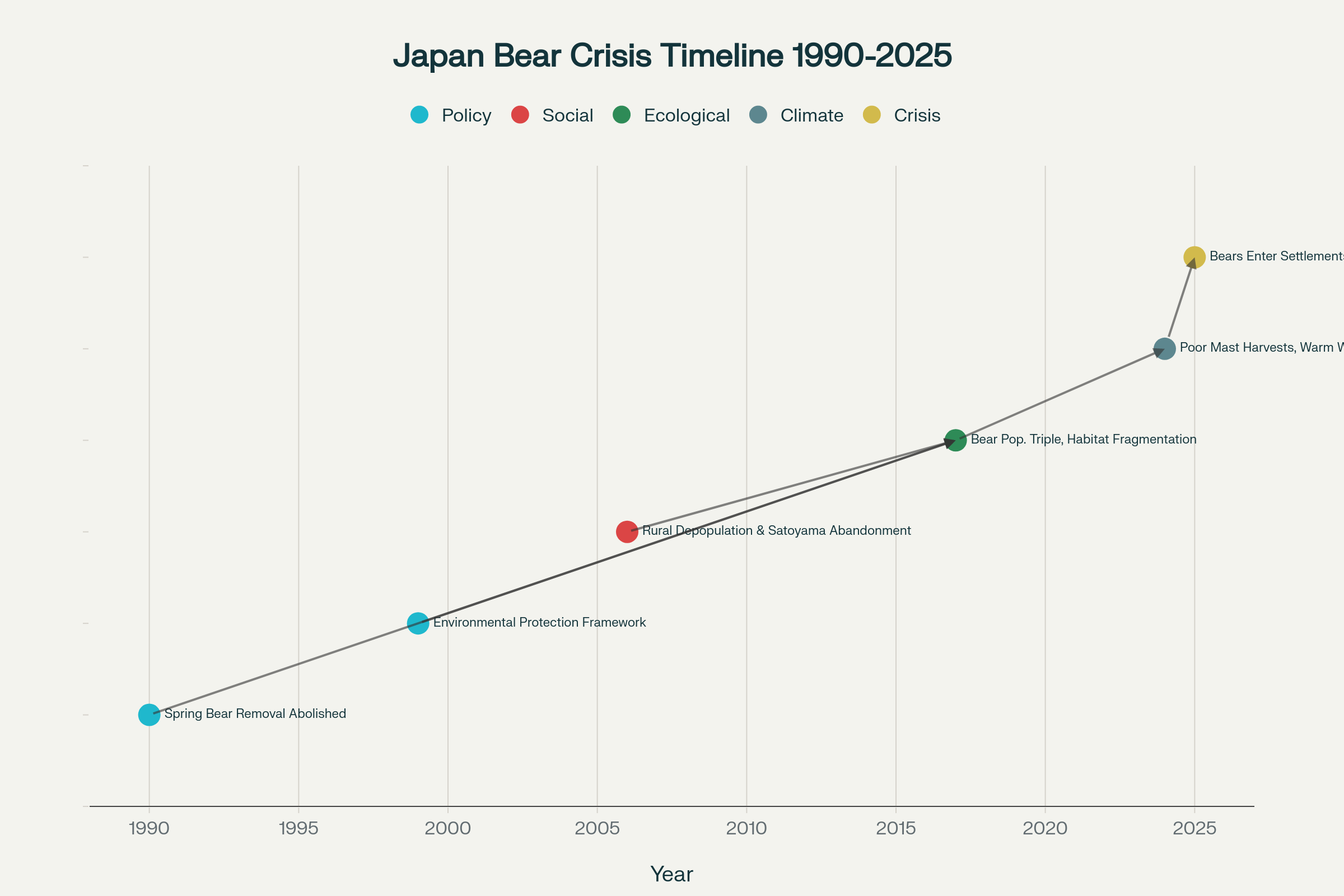

Japan's bear crisis began with conservation success that evolved into ecological miscalculation. In 1968, Japan initiated the "Spring Bear Removal" campaign—a systematic hunting program that devastated bear populations, particularly in Hokkaido. By the 1980s, hunters reported dramatic population declines, and the species faced genuine extinction risk in certain regions.[10]

In 1990, the Spring Bear Removal was abolished. More significantly, in 1999, Japan introduced a new environmental protection framework that prioritized bear conservation. The policy was well-intentioned: bears were an important part of the ecosystem, and their extinction would represent an irreplaceable loss.[11]

The result was dramatic. Hokkaido's brown bear population more than tripled from approximately 4,000 in 1990 to 12,000 by 2025—a 200% increase. Japan's Asiatic black bear population grew from around 30,000 to 44,000—a 47% increase. Today, the government estimates the total bear population exceeds 54,000 animals.[3:1][4:1][12][13]

Multi-Causal Timeline: Converging Factors Behind Japan's Bear Crisis

This recovery was ecologically appropriate given the species' near-extinction risk. However, the model failed to account for a transforming human landscape.

Factor 2: Rural Depopulation and Habitat Collapse

While bears were successfully recovering, rural Japan was experiencing catastrophic demographic collapse. Since the 1970s, younger generations have migrated to urban centers in search of employment and opportunity, leaving behind aging communities in rural and mountainous regions. This pattern has accelerated dramatically in recent decades.

Japan now has approximately nine million empty houses, primarily in rural areas, with more than 20% of homes sitting vacant in some prefectures like Wakayama and Tokushima. This depopulation has had an unexpected and devastating ecological consequence: the collapse of the satoyama landscape—the traditional buffer zone of managed farmland and forests that historically separated mountain wilderness from human settlements.[14]

For centuries, satoyama landscapes represented a carefully cultivated ecological mosaic. Local communities maintained these spaces through active stewardship: harvesting timber and charcoal from coppices, collecting leaves for mulch, managing rice paddies with precise water systems, and maintaining orchards and gardens. These human-managed landscapes supported extraordinary biodiversity and served as a critical barrier that kept bears in their mountain habitats.[15][16]

With depopulation, this entire system collapsed. Abandoned orchards now offer bears abundant food without human resistance. Fallow fields and overgrown gardens have become "green corridors"—continuous pathways of vegetation that guide bears directly from mountain forests into residential areas. Untended persimmon trees, chestnuts, and other fruit trees attract bears with guaranteed nutrition, while the absence of human activity removes the noise, smoke, and general presence that once kept bears away.[1:1]

Research published in Nature Sustainability confirms that Japan's depopulation is not leading to environmental recovery as might be intuitively expected. Instead, the changing use of agricultural land through abandonment—rather than direct human population decline—is driving biodiversity loss and accelerating wildlife-human conflicts. The study analyzed over 1.5 million citizen-science observations and concluded that human abandonment of traditional land management practices creates ecological conditions favorable to bear movements toward human zones.[17][18]

Factor 3: Climate-Driven Food Scarcity

Beyond the long-term structural changes, 2025 has witnessed an acute climate-driven crisis. The immediate trigger for the current surge is a historic failure of the mast harvest—the annual production of acorns and beechnuts that constitute the bear's primary food source.

The Tohoku region, where most bear incidents occur, experienced what experts classified as a "severe poor harvest" in 2025. This was not an isolated weather event but reflects broader climate patterns. Beech nut production depends on complex environmental conditions including spring temperature, summer heat, and autumn moisture. Climate change is disrupting these cycles, leading to more frequent mast failures.[19][20]

For bears preparing for hibernation, the autumn season represents critical hyperphagia—a period of intensive feeding to accumulate fat reserves for the five-to-six-month winter dormancy. When the normal food supply fails, bears have no evolutionary template for finding alternative nutrition. They cannot import food from other regions or significantly modify their dietary preferences within a single season. Instead, they venture into human territories, where garbage, stored food, and agricultural products offer caloric alternatives.[21][19:1]

Experts such as Associate Professor Maki Yamamoto of Nagaoka University of Technology had long warned that such crop failures would inevitably drive bears out of mountains in search of food. When hungry bears encounter humans, they abandon their natural fear-based avoidance behavior.[19:2]

Factor 4: Disrupted Hibernation Cycles and "Sleepless Bears"

Climate change introduces a further complication: warmer winters are disrupting the hibernation cycles upon which bear survival depends. Teruki Oka, head of the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, explains that hibernation requires specific physiological conditions—sufficiently low body temperatures and adequate fat reserves. When winter temperatures remain unusually warm, bears' body temperatures cannot drop enough to trigger true hibernation.[22][21:1]

Additionally, bears that failed to consume sufficient food during autumn cannot enter hibernation even if winter conditions would normally trigger it. These "sleepless bears" or "non-hibernating bears" remain active throughout winter, when food is extremely scarce, driving them to continue foraging in human areas.[21:2][22:1]

Research on North American bears demonstrates that temperature increases directly correlate with shortened hibernation periods. For brown bears, every 4°C increase results in bears leaving their dens 10 days earlier. Japanese researchers warn this phenomenon is now occurring in Japan.[20:1][23][21:3]

Furthermore, some bears—particularly brown bears with carnivorous preferences—naturally avoid hibernation in favor of hunting. When natural prey is scarce due to winter conditions and poor mast harvest, these bears' predatory behaviors shift toward human areas and livestock.[22:2]

Compounding Factors: Aging Hunters and Urban Bear Adaptation

Two additional factors amplify the crisis's severity. First, Japan's reliance on recreational hunters to manage bear populations is becoming unsustainable. Hunting culture in Japan is aging rapidly, with a declining population of skilled hunters who traditionally managed wildlife populations. Municipalities lack the specialized expertise to respond to modern bear conflicts, particularly in urban settings where conventional hunting is unsafe.[12:1]

Second, there is evidence that bears are beginning to lose their natural fear of humans through repeated exposure to human environments without negative consequences. When bears successfully obtain food from human areas—particularly abandoned agricultural lands—they rapidly learn that humans pose minimal threat. This behavioral adaptation is accelerating the crisis, as bears increasingly associate human settlements with food availability rather than danger.[19:3][24]

Military Deployment: A Symptom, Not a Solution

In response to the crisis, the Japanese government announced on November 6, 2025, the deployment of Ground Self-Defense Force troops to northern regions experiencing the worst bear attacks. This deployment represents an extraordinary acknowledgement of the crisis's severity—the first time Japan's military has been deployed domestically for wildlife management.[3:2][4:2][25]

Defense Minister Gen Nakatani explained the deployment as necessary because bears "have even appeared inside private homes and caused deaths" and "are coming out into human settlements." The troops will provide shooting skills and personnel to support municipalities struggling with inadequate hunter numbers and expertise.[25:1]

However, this military response addresses symptoms rather than causes. Killing individual bears cannot resolve the structural factors driving the crisis: the expanding bear population, the collapsed satoyama landscape, ongoing climate change disrupting food systems and hibernation, and the continued depopulation of rural regions.

Bear expert Mika Maekawa of the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology warns that killing bears does not address root causes. Indeed, population culling alone may prove counterproductive if it reduces competition among remaining bears, potentially allowing them to range more widely and successfully exploit human resources.[26]

Long-Term Implications: An Unreconcilable Conflict?

The bear crisis reveals fundamental tensions between ecological conservation and human welfare. Japan's environmental protections successfully prevented bear extinction—an important conservation achievement. However, these protections were implemented within a broader social context of dramatic rural depopulation and agricultural abandonment, creating conditions where recovering bear populations inevitably expanded into landscapes humans were vacating.

This raises profound questions about Japan's future landscape management. Can satoyama buffer zones be restored when rural communities are demographically collapsing? Can bears be effectively managed when the hunting culture necessary for population control is disappearing? Can climate change be addressed quickly enough to restore natural food systems and proper hibernation cycles?

Some researchers suggest Japan faces a choice between three futures: reinvesting in rural communities to restore human presence and satoyama management; accepting permanent depopulation but maintaining abandoned landscapes through intensive government-funded management programs; or retreating into consolidated urban areas while allowing bears to reclaim increasingly wild territories.[24:1][26:1]

Each path presents enormous challenges. Rural revitalization would require economic transformation in regions where young people have no employment prospects. Government-funded land management would require sustained political will and enormous budgets. Accepting territorial retreat would mean acknowledging the permanent loss of cultural landscapes that have defined Japanese identity for millennia.

The crisis also challenges the assumption that successful species conservation automatically improves human welfare. Bears have been successfully conserved; human communities have not. The absence of integration between conservation policy and social policy has created a profound misalignment.

Conclusion: A Systems Crisis

Japan's bear attack crisis is not simply a wildlife management problem, nor is it reducible to any single causal factor. Rather, it represents a systemic failure emerging from the intersection of four distinct developments: ecological recovery of bears following 30 years of protection, catastrophic depopulation of rural Japan over 50 years, climate change-driven disruption of food systems and hibernation cycles, and loss of traditional knowledge and hunting culture.

The crisis illuminates a profound tension in modern conservation: it is possible to save a species while the human communities that historically coexisted with that species simultaneously collapse. The resulting configuration—increasing bear populations in an increasingly human-abandoned landscape—creates unprecedented opportunities for conflict.

The military deployment represents not a solution but a symptom of deeper system failure. Addressing the bear crisis requires not merely more hunters or better traps, but a fundamental reimagining of rural Japan's future. This requires either restoring human presence in depopulated regions (revitalizing satoyama management and rural livelihoods), maintaining abandoned landscapes through intensive management by government workers, or accepting a reconfigured relationship where bears reclaim territories and humans retreat further into consolidated urban centers.

Until these underlying structural issues are addressed, 2025's record-breaking statistics will likely be exceeded in coming years, particularly if climate change continues to disrupt mast harvests and warm winters that prevent proper hibernation.

References

© 2025 P.C. O’Brien (Eden Eldith) — Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-10-28/japan-bear-population-could-be-culled-by-military/105940686 ↩︎ ↩︎

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/11/6/japan-deploys-the-military-in-north-to-battle-surge-in-bear-attacks ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

https://www.cnn.com/2025/11/06/asia/japan-bear-attacks-military-sdf-intl-hnk ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

https://www.independent.co.uk/tv/news/japan-bear-attacks-troops-deployed-video-b2859710.html ↩︎

https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/japan-sends-troops-combat-deadly-wave-bear-attacks-2025-11-05/ ↩︎

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2025/11/05/japan/society/bears-ruin-autumn/ ↩︎

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2025/09/12/japan/black-bear-record-high/ ↩︎

https://english.news.cn/asiapacific/20251016/3c7ddf4ca8ba419e98525d71f312acfa/c.html ↩︎

https://bioone.org/journals/ursus/volume-2024/issue-35e25/URSUS-D-23-00016.1/Harvest-based-demographic-estimation-of-a-brown-bear-population-on/10.2192/URSUS-D-23-00016.1.full ↩︎

https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/bear-attacks-are-rising-in-japan-ageing-hunters-are-on-the-front-line ↩︎ ↩︎

https://www.npr.org/2025/11/06/nx-s1-5600582/japan-bear-attacks ↩︎

https://geographical.co.uk/wildlife/depopulation-is-reshaping-japans-countryside-and-threatening-biodiversity ↩︎

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/26395916.2020.1837244 ↩︎

https://poorprolesalmanac.substack.com/p/the-satoyama-landscape ↩︎

https://modernsciences.org/japan-depopulation-biodiversity-loss-june-2025/ ↩︎

https://worldinsight.com/news/environment/the-worst-autumn-on-record-when-japans-bears-invade-human-settlements/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

https://earth.org/climate-change-is-threatening-the-survival-of-bear-speices/ ↩︎ ↩︎

https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/japan-wildlife-experts-warn-of-bears-who-do-not-hibernate-in-the-winter-amid-spate-of-bear-attacks ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20231125/p2a/00m/0li/004000c ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/world/archives/2025/10/17/2003845639 ↩︎ ↩︎

https://news.sky.com/story/japan-sends-in-troops-to-help-tackle-deadly-bear-attacks-13464251 ↩︎ ↩︎